James Fox, Founder Of The Prison Yoga Project, On Bringing Yoga Into Action And Into Service

By Ashley Shires

The Prison Yoga Project helps incarcerated men and women build a better life through trauma-informed yoga with a focus on mindfulness. It helps prisoners make grounded, conscious choices instead of reactive ones. These skills are critical because in the United States alone, 1 in 100 adults are currently in prison, a total of 2.25 million men and women. And recidivism rates are incredibly high: 60% of people released from prison will return within three years.

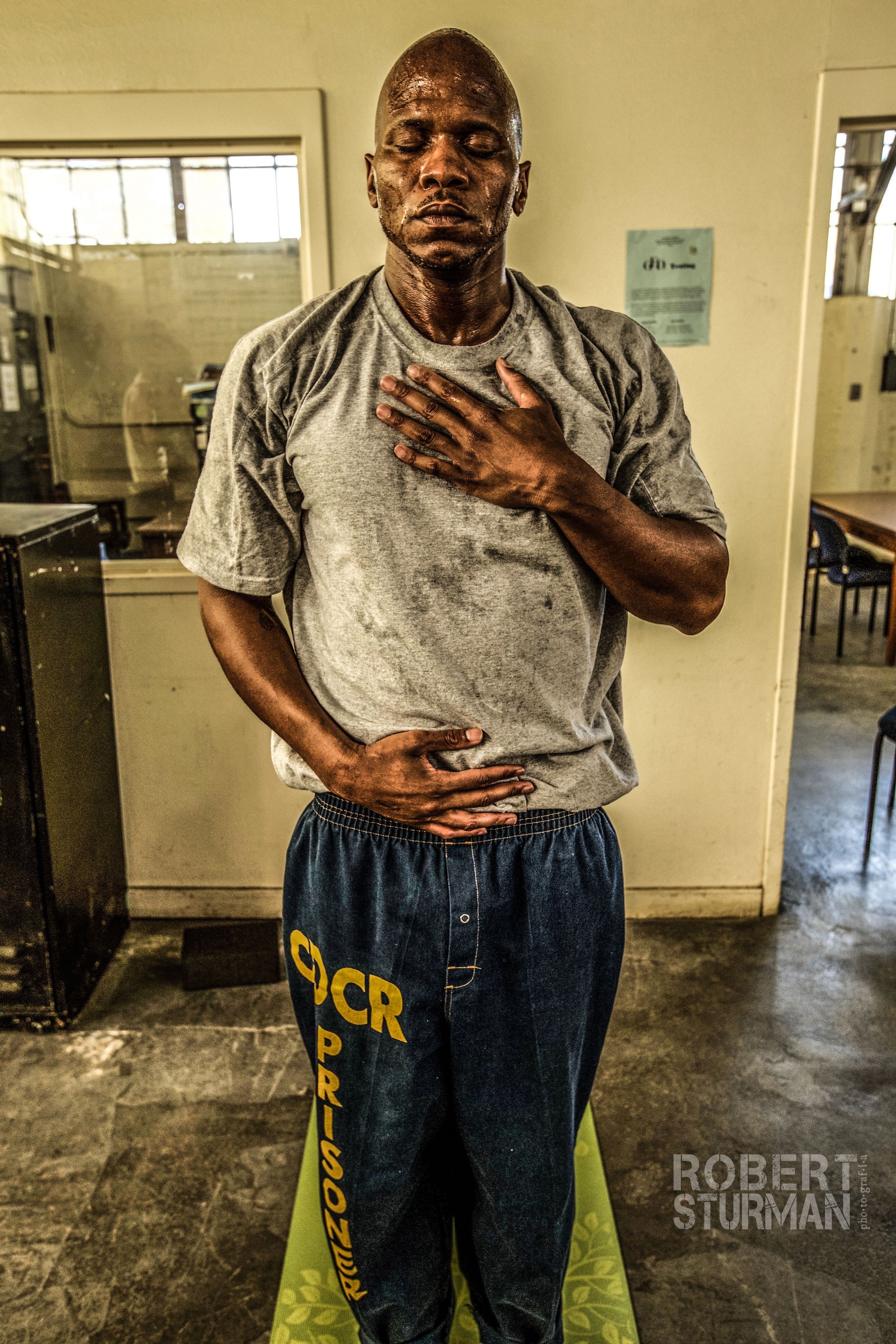

James Fox, founder of the Yoga Prison Project, says that most prisoners suffer from complex trauma experienced early in life, including abandonment, homelessness, physical and sexual abuse and domestic violence. A mindful, embodied yoga practice can have an incredible impact, alleviating the symptoms of trauma so that behavioral issues can be addressed. Students are taught to restore the connection between mind, body and heart, increasing self-compassion and empathy for others. They learn impulse control, which helps them take responsibility for their actions and reduces their chances of returning to jail.

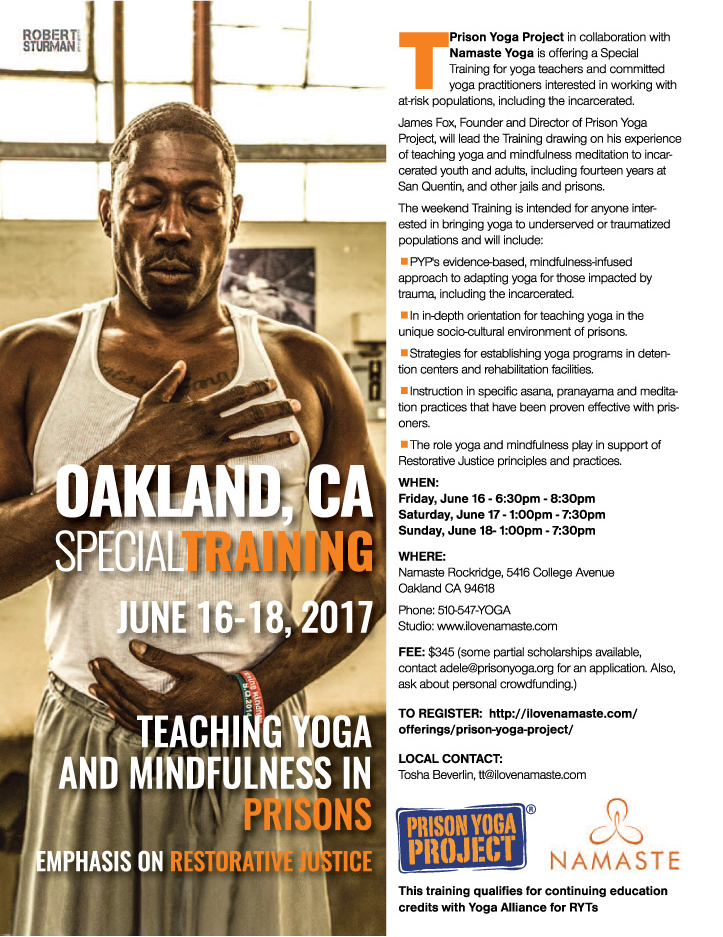

Since 2011, the Prison Yoga Project has trained over 1,500 instructors who are now teaching classes in over 105 prisons in 23 states. But the need for yoga in prisons is still enormous. SF Yoga Magazine caught up with James to learn more about how the Prison Yoga Project evolved and what students can expect from the trainings.

How did you first start teaching yoga in the prisons?

When I became a yoga teacher, I was very interested in bringing yoga to populations that weren’t being exposed to it, who weren’t exposed to the psychological and emotional benefits. I started out teaching in a residential facility for youth, and within a year, I was contacted by a nonprofit that was bringing a mindfulness program to Bay area juvenile facilities. They asked if I would add a yoga component, and I said yes. The next year, a nonprofit was putting together a prisoner rehabilitation program, and they wanted to add a body/mind integration component. I was asked to set it up at San Quentin in 2002.

As I like to tell the guys at San Quentin, you weren’t part of my 10-year vision, but you were an answer to my prayers. I wanted to bring yoga to populations that weren’t being exposed to it, and I realized that what I was doing was karma yoga, bringing yoga into action, into service. My prayer was, ‘how can I be of service?’ and then I paid attention. I followed the guidance that was given to me, so to speak.

How is teaching in prisons different from teaching in a yoga studio?

When I first started at San Quentin in 2002, there was no model for it – there was no place to learn how to do it rather than to follow my intuition. I did a training with a senior Iyengar instructor from India who runs a nonprofit center in India that serves people dealing with addiction. I was inspired by studying with him to be of service with the yoga that I wanted to teach. But there wasn’t an orientation or methodology for teaching yoga in prisons when I started. And I feel pretty strongly that we teachers going into prisons should have a standard ideology, an understanding of the impact of trauma. The understanding that 99% of your students will have unresolved trauma that shows up in behavioral problems and addiction problems.

What kept you going in the beginning?

Once I started experiencing the personal benefits, the rewards of being of service, that’s what really propelled me. That’s important about karma yoga – you do it without expectations of an outcome. You’re there to truly be of service and offer something that you know, a skill that helps them with the issues that they face. That’s what eventually got more guys interested in the class. I could find the practical topics that applied to their lives – the balance between the meditative, conscious breathing and the physical part of the practice. It’s a multicultural population and from varying religious backgrounds – it’s important to keep it real and practical and secular.

How quickly did the program grow?

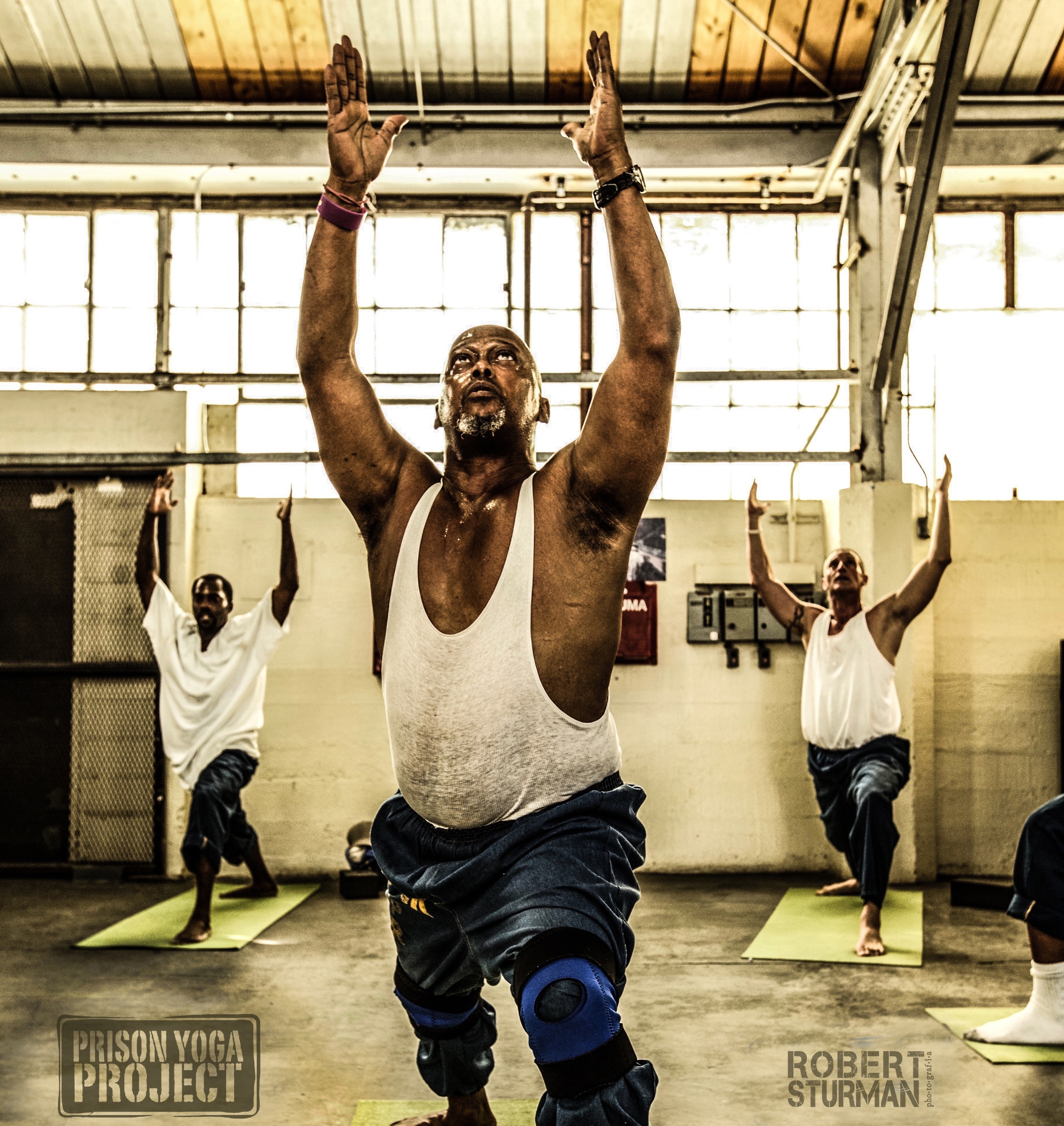

When I started out, I had about five guys who came to class, about the bravest guys in the prison. The impression of yoga in prison back then – you don’t even want to hear what kind of words the other prisoners used. But I felt grounded enough to do it. And everything in prisons spreads through word of mouth. It wasn’t the administration saying, ‘this class would be really good for you.’ It was the prisoners saying, ‘you should check this class out, this is for real.’ Now we have four different classes a week at San Quentin, serving about 60 men, and we have a waiting list of over 50 guys waiting to get in the class.

What feedback do you get from the prisoners?

The number one benefit I hear is decreased stress and anxiety. Prisoners new to the program report having the best night of sleep they’ve had in a long time. They experience relief from chronic pain from lower back and shoulder issues. They lessen their dependence on medication. They also say that they really learn how to deal with their anger. That is one of the most important benefits: They are able to check themselves before they go off. A yoga program has the potential to reduce violence.

And what feedback do you get from the yoga instructors?

Of all the teachers who are teaching classes, I haven’t heard of one serious incident that has happened with anyone, which flies in the face of the way people in prisons are portrayed. The general population doesn’t realize how grateful prisoners are for people to come in and volunteer their time, especially when they reap the physical, social and psychological benefits.

What does the teacher training focus on?

The first day of training focuses on the emotional and psychological issues prisoners bring to class and the reality of what the prison environment is really like. Afterwards, some people think, hmm, maybe I don’t want to teach in prison. And I’m fine with that. What I hope is that they become inspired to teach some other type of karma yoga. Others who want to do the work, but had no idea what it would be like, come away feeling much more confident.

For example, I just came back from a training in Chicago, and there was a very nice, very experienced and attractive female yoga teacher. She said at the introduction that she would like to go into a jail or prison, but that she wasn’t interested in teaching men. But 93% of the incarcerated are men and 85% of yoga teachers are women. We need women to teach men – because of the numbers, clearly, but more importantly, because of what women can bring to men in the terms of yoga practice. At the end of the training, the female yoga teacher came up to me and said, ‘thank you – I want to teach men. I’m convinced as a result of this training that I can teach men.’ She is now going to shadow a male teacher at Cook County.

What do women bring to this methodology?

They often don’t focus as much on asana. Men in prison are already challenged physically – but they’re not challenged enough emotionally. Women can bring that sensitivity, that feminine quality of being more in touch with themselves from an emotional perspective. Male prisoners can perhaps open up and soften some and receive some of what a female yoga teacher has to say. With male teachers, there’s an immediate suspicion, competition, who is this guy? You want to model for men in prison that there’s another way of being a strong man.

Can you talk a little about the teacher collectives that have formed in the wake of your trainings?

Every time I do a training in a local area, the participants start a FaceBook page to help each other stay more connected and share best practices. But we are now also planning to launch a sangha portal on our website, which will be much more meaningful. It will give us the ability to update posts as we continue to develop the methodology. We will be able to provide more information and training. But building a portal takes money. We currently have a $5,000 grant that we are asking to match right now, and that money will go towards finishing the sangha portal.

Any last words you’d like to share about your yoga trainings?

Universally people go away from the training realizing that this is not just applicable to prisons and people with trauma. It deepens teachers’ understanding of what yoga is really all about. It changes people’s approach in their public classes, taking them back to the roots of their practice, changing their teaching style for the better.

To learn more about the Prison Yoga Project, visit www.prisonyoga.org.